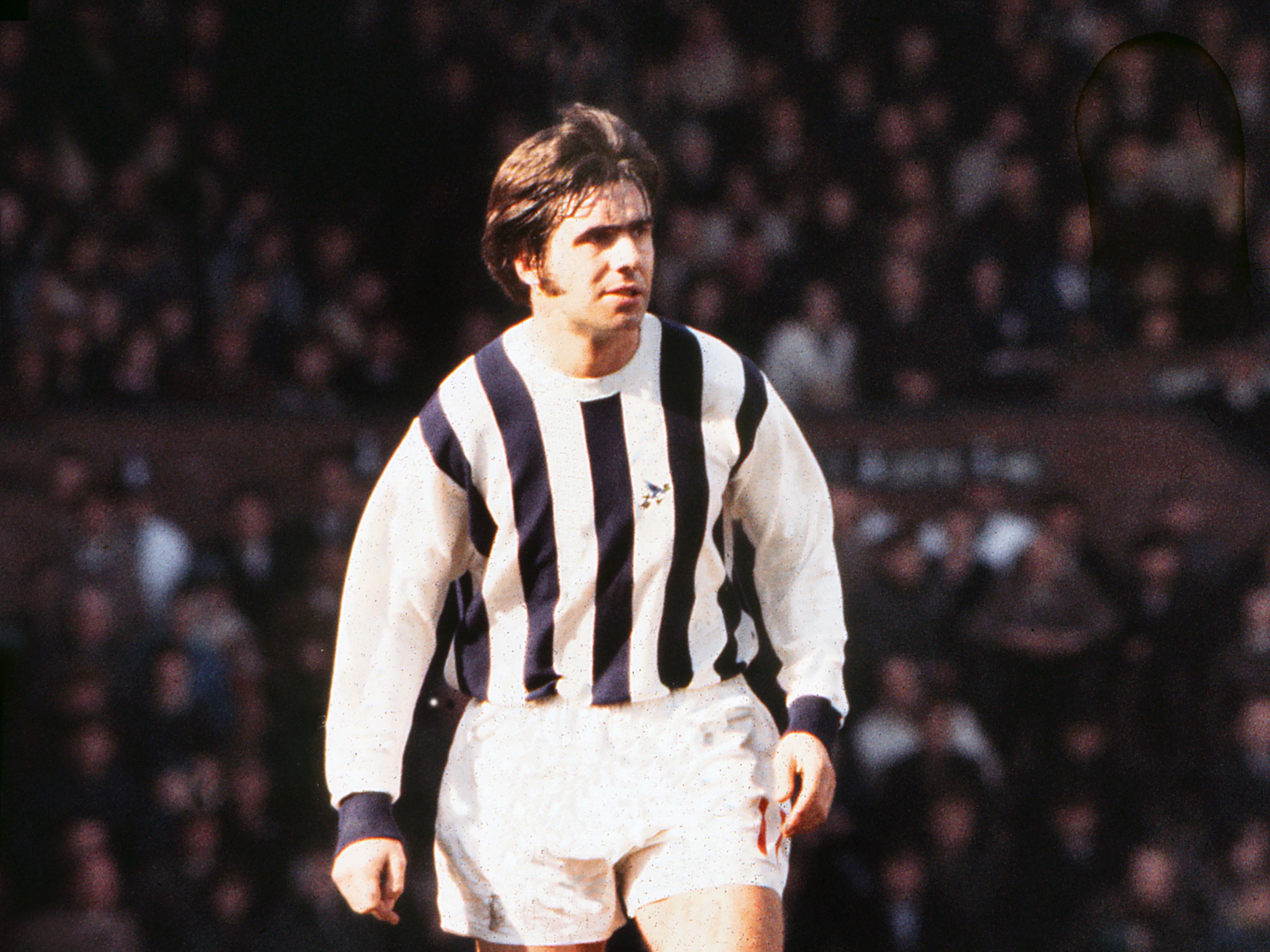

Highly-respected West Bromwich Albion author and historian Dave Bowler pays tribute to his friend, colleague and hero, Bobby Hope, who passed away on Friday at the age of 78.

The elevation of Sir Robert Hope to the great dressing room in the sky takes from us another of that highly select band of special men who could stake a genuine claim to a place in the all-time Albion XI.

If you value aesthetics in your football, if you want it silky, easy on the eye, then watching Bobby Hope play the game was something approaching heaven, for the all-encompassing range of his incisive vision was paired with a seemingly effortless ability to capitalise on it with a perfect pass.

Those delivery companies that advertise that they can get your parcel to its destination, however near or far? They pinched that idea off Bobby, a purveyor of the football from anywhere, over distances long and short, delivered precisely onto the head of a drawing pin. Tell me about a better passer of a football than Bobby Hope in his prime and I’ll explain the error of your ways - fair enough?

After making his debut for Albion as a 16-year-old in a 1-0 win over Arsenal in the final game of the 1959/60 season, Hope became the creator supreme of that 1960s side that scored goals as if they were going out of fashion. Placing the ball into the path of Clive Clark’s run, onto Jeff Astle’s noggin, or teasing it into position for Tony Brown to thrash another volley into the net, Bobby’s imagination, his vision and his ability to turn those mental pictures into vibrant reality was the engine of that side’s success.

Brown, Astle and Clark might have scored something like 400 goals between them during Hope’s time at The Hawthorns, but if anybody could have been bothered keeping stats for assists in those days, Bobby would have notched a couple of hundred to go with his 42 goals before he left the club in May 1972. Which would have made him worth about £120million today – if anybody could afford to pay him that much a week.

The problem when you talk about footballers, especially those midfield playmakers who are a joy to watch, is that people assume they are also a bit soft, a pushover. Not Bobby Hope. Bobby was such a good footballer because yes, he had the natural talent of what the Scots call a “tanner ba’ player”, honed as a kid on the streets of Drumchapel, but beyond that, he had the spirit of the natural born winner, a quality that never left him.

Hope appreciated skill, technique, intelligence just like the rest of us, but he had no time for any nonsense that says that entertaining is more important than winning. He never believed it when he was a player and he didn’t believe it later on when he returned to the Albion to work in the youth and then the scouting set ups. If you can do both, perfect. But if you couldn’t, Bobby would have chosen winning every time.

That was ever the paradox of Bobby Hope, both an arch-pragmatist and supreme artist, but it was that combination that made him such a wonderful footballer. The brilliance was alloyed with spikiness, a competitive streak that meant he could not only survive the midfield minefield in an altogether more physical and brutal era than today’s, but also had the drive and determination to prove himself the very best.

That drive expressed itself in the sublime football that Hope produced across the football fields of England and beyond when Albion dipped a toe into the European competitions. For he was nothing if not a courageous footballer, in the sense of trusting that inordinate talent, of wanting the ball and using it, always making himself available, however tightly marked, however extreme the pressure. That’s footballing courage, giving your mate an option rather than leaving him to look at a sea of retreating shirt backs.

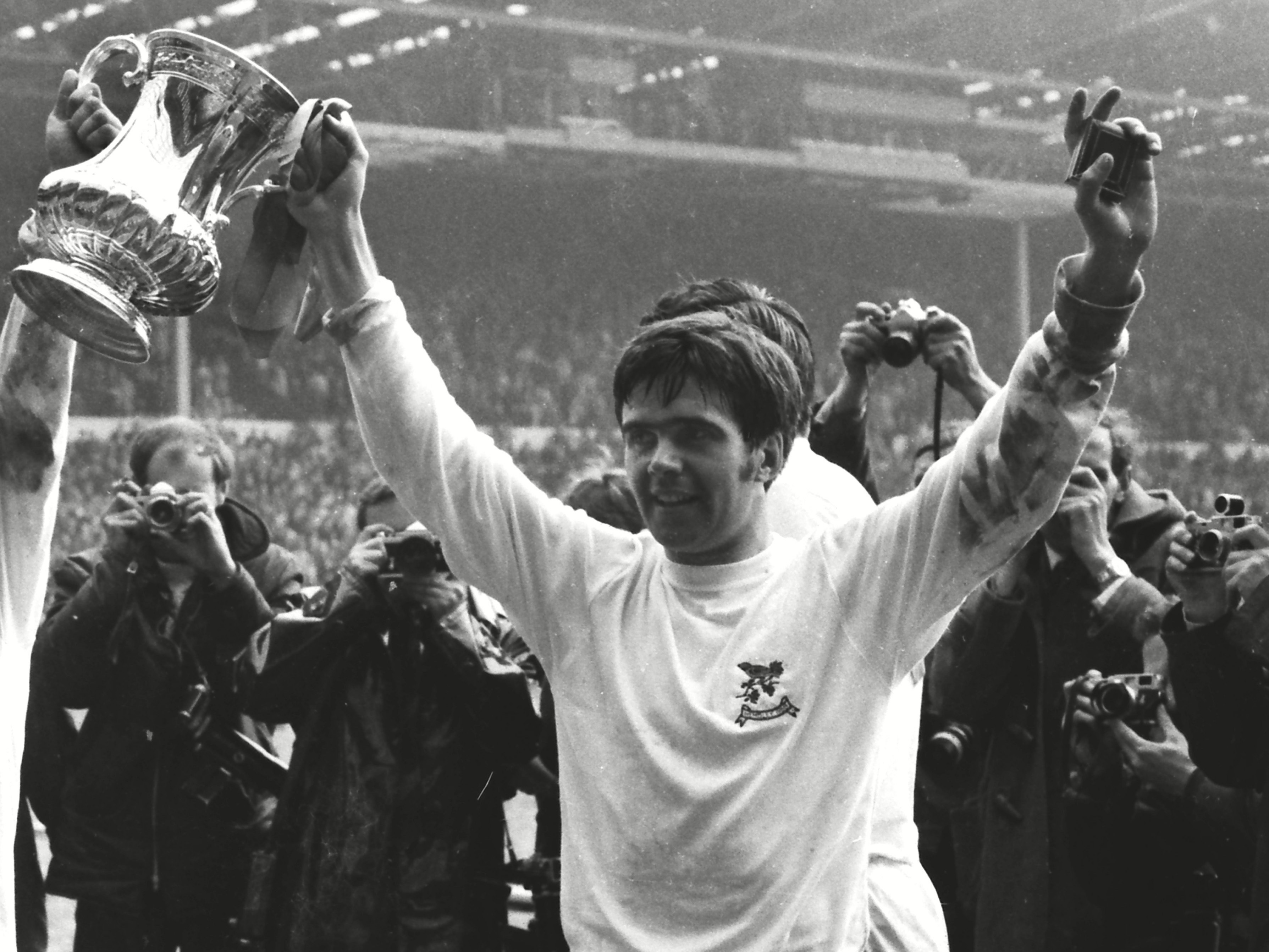

Bobby always wanted the ball and he always used it to great effect when he had it. He was the fulcrum of that Albion side that was the best cup fighting unit in the land in the second half of the 1960s, scheming away at its heart as we won the League Cup in ’66, reached the final in ’67, won the FA Cup of 1968, went all the way to the semi-final again in ’69 and then to another League Cup final in 1970.

Four cup finals in five seasons, two won, the greatest prolonged era, rather than single triumph, since the days of Stoney Lane, back in the infancy of both the club and of organised football. In no small part, we were able to achieve those triumphs because we had Bobby Hope in our ranks, one of the greatest footballers we’ve ever had the privilege to employ.

God might not bestow immortality on any of us, but the Throstletariat can. Bobby Hope, an Albion immortal. Never forget him.

Rest easy, Sir Robert.