Thursday, January 30 2025 marks 125 years since West Bromwich Albion Football Club purchased the land for our home, The Hawthorns.

Highly-respected author and historian Dave Bowler tells the fascinating story of how the Baggies swapped Stoney Lane for the Shrine...

January 30th 1900. Queen Victoria was in the 63rd, and final, year of her reign. Lord Salisbury was Prime Minister. The second Boer War was raging. We were still 28 days away from the creation of the Labour Party and 24 hours from the copyrighting of the ‘His Master’s Voice’ illustration of Nipper the dog. But, as we shall see, these are mere trifles compared with the real history of the day. If you’re sitting comfortably, we’ll begin…

At that time, West Bromwich Albion were, undeniably, among the early giants of English football. The Throstles had won two FA Cups, reached three other finals and kicked off the Football League’s history, as well as winning plenty of local competitions, but there is more to running a business than just footballing glory. The difficult sums need to add up as well.

Things were coming to a head as the 19th century was heading towards its close along with the end of the Victorian age. A new world was on its way and, as far as football was concerned, it would increasingly revolve around pounds, shillings and pence. On that front, Albion’s rickety old Stoney Lane home made no real sense.

In April 1899, with the club struggling to make ends meet, The Free Press painted a pretty bleak picture both for us and the wider game. “The fact is that with the high prices now ruling for players, and the transfer system, the Albion are placed at an enormous disadvantage in their comparatively poor financial position in securing really good men. The clubs with the longest purse have the best chance of securing the cleverest players. These demands for high wages are gradually killing the game in many towns”. And they say history can teach us nothing.

The problem was simple. You might be able to cram supporters into Stoney Lane for one off cup games, but beyond that, it was lacking in the facilities needed to make it a welcoming venue. Additionally, the ground was only held on a short-term lease and, after some initial enthusiasm for the site, which included the building of the Noah’s Ark grandstand, the club directors soon refused to put any more money into improvements given this was not a permanent home.

With other clubs growing quickly by investing the money now coming in from the better attendances into stadium infrastructure, it meant Albion had perhaps the worst ground in the Football League, certainly in its top division, while the team was also in decline. Albion had survived the drop to Division Two in 1896 only by virtue of coming through the end of season “Test Matches” against Liverpool and Manchester City, an early version of the play-offs.

Stoney Lane was holding the club back and, while in the spring of 1899 Albion entered into a further 12 month lease on the ground, it was clear they needed to move on. Yet nothing is ever quite that simple in football, particularly as we are all so wedded to our traditions and our history. While the directors had already proposed a move from Stoney Lane well before things came to a head in 1899, as the Birmingham Gazette reported, it was an idea that for some seemed to be too far ahead of its time.

“The suddenness of the proposal was too great for a few individuals and a sentimental attachment to the old Stoney Lane ground caused opposition to be raised. Moreover, a number of gentlemen with interests in the vicinity came forward with a proposal to spend £2,500 on the old ground with the object of so improving it as to attract a greater number of people. The opposition was carried to such an extent by interested parties that eventually the owners withdrew the offer of the ground and the whole thing fell through.”

Stuck in Stoney Lane, financial matters deteriorated so badly in the 1898/99 season that a meeting of the club was called to see if it could continue to operate at all. At that meeting, those who had earlier offered the £2,500 were called upon to see if their promise remained good. If you’ve ever paid any attention to high finance, you will not be surprised to learn that it did not, and that only around £300 was now on offer to improve Stoney Lane, chicken feed even then. A move was crucial if Albion were to survive. The club had reached a point of no return, from where it simply had to speculate if it was going to accumulate.

But if the move was on, where, exactly, was the club to go?

As the Birmingham Gazette noted, “It was useless looking for a ground in the direction of Hill Top or Great Bridge, as the neighbouring towns of Dudley and Wednesbury, from which in past years a large proportion of the club’s supporters have been drawn, have each now got successful junior football clubs of their own which attract 4,000 or 5,000 spectators to witness their matches. The reduction of the fare of the cable trams to ‘one penny all the way’ and the enormous increase in the populations of Handsworth and Smethwick has made it abundantly clear that any removal of the ground to prove a success must be in the direction of Handsworth”.

With Albion desperately scouring the locale for an appropriate site for a new ground, the timing could not have been better when, on December 5th 1899, a letter from Benjamin Karliese, the secretary of the Sandwell Park Colliery Company dropped on to the Albion’s doormat.

“My Board direct me to offer you a lease of the piece of land forming the corner of Halfords Lane and the Birmingham Road, about 10 acres (less sufficient land next to the “Oaklands”, to make a road across, 40 to 50 feet wide) for 14 years at a rental of £70 per annum for the first seven years, and £80 per annum for the second seven years. The West Bromwich Albion Football Club Company to have the option of terminating the lease at the end of the first seven years on giving such notice as may be mutually agreed.

“The Football Club Company to pay to the Company one-third of the revenue that may be derived from any hoarding that may be erected by the Club on the land in question during the existence of the lease, the Club retaining two-thirds of the revenue for the cost of erecting and maintaining the hoarding and collecting the revenue arising therefrom.

“My Board will reserve full powers for working the mines under and adjacent to the land, without being liable for damage to surface or erections thereon, and would require the covenants usual in their Leases to be embodied in this. It is understood that this offer is left open for your acceptance till 1st February, 1900, but if practicable my Board would be glad of a decision earlier”.

To translate, if your centre-forward suddenly dropped 250 feet through a hole in the six-yard box and down to the mine workings below, it would be, in a very real and legally binding sense, the club’s problem.

The Birmingham Gazette noted that this approach was a particularly pleasing development and that the plot in question fitted the bill perfectly, for the proposed site had good access, wide roads coming up to the ground from West Bromwich, Smethwick and Birmingham, although the later arrival of the motor car meant that easy post-match departures would eventually become a thing of the dim and distant past. But back then, with the main tram routes into Birmingham running right past the site, the perfect location had dropped into the laps of the Albion directors.

“A suitable piece of land was noted at the corner of Halford’s Lane on the main road, about halfway between the New Inns at Handsworth and the Dartmouth Hotel at West Bromwich. Its situation is believed to be even better than the ground near the Beeches Road which was proposed [in 1898], being easier of access from large centres of population.

“On the Handsworth side of it, a new street will be cut leading into Island Road, so that entrances to the ground can be made from three separate and wide roads, and with ten acres of land there will be abundance of room for all requirements. It will be easy of access from all parts, and it should be the commencement of a new lease of life for the club. The ground will have to be drained and relaid and suitable stands for the accommodation of the people provided. We are not in a position to state definitely as yet how the money will be raised, but we understand the directors can see a way of doing this without touching the funds of the club”.

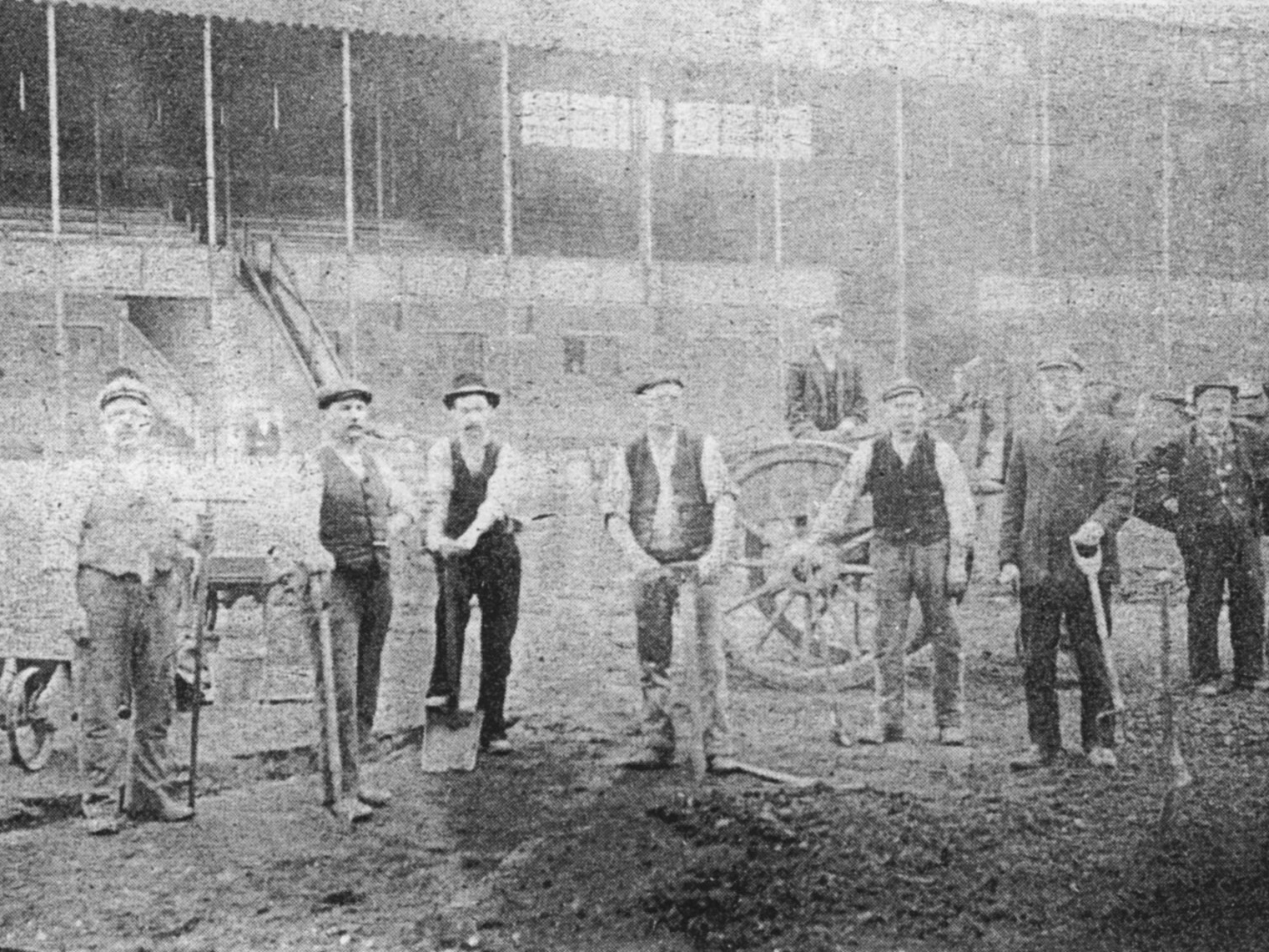

Essentially, the plot was an area of marshland in a rural location. There was a brook running diagonally through what was effectively a meadow, the brook forming a border between Smethwick, Handsworth and West Bromwich. The Woodman Inn (of blessed memory) was on the Handsworth side, along with a blacksmith’s forge and a few houses. At the Smethwick end was a large house, Oaklands, and a garden nursery. A large private house was to one side of the land. It later became The Hawthorns Hotel and housed many Albion players – the great Ray Barlow got word of his first England call up there – and is now Greggs. From the sublime to the vegan sausage roll.

The amount of money available for undertaking all this work was a mere £1,800, but this did not deter the directors of the club who realised this was the route to the club’s ultimate salvation, the chairmanship of the newly installed Major H. Wilson Keys particularly crucial in driving the idea through. But we like a bit of brinkmanship at West Bromwich Albion, and so it was not until January 30th 1900 that the club accepted the proposal, signed the papers and the move became a reality.

But what to name the new place? Frank Heaven, Albion’s secretary-manager of the time, had done a little research on the site and had been told that in previous years, it had been part of an estate covered in trees, bushes and wildlife. Given the relationship between the throstle and the most prevalent of those trees, what better name than that of the original estate?

Welcome to The Hawthorns.